How To Be A Good Winner

The subtitle of your book is ‘The Power of Decency in a World Turned Mean’. What do you mean the world has gone mean, David?

Whenever there is a new technology, good people and bad people try to use it. At first, unpleasant people will take advantage of it but after a time we learn how to control it. When telephones first came in, people got interrupted all the time and it was obnoxious, then answering machines came along to balance this out. Text messaging was problematic at first too; now WhatsApp is so much better for many group conversations because messages can sit there, several people can look at them without everyone getting inundated. Before seat belts, other safety devices and rules against drunk driving, cars were catastrophic. That’s where we are with the internet today. From hacking to social media, it is easy for terrible people to take advantage of it. Our current leader in America, for example, would not have achieved his position without Twitter.

Is the meanness here to stay?

I'm sure in the next couple of years we will see social media becoming better controlled. Of course, in the future there will be other technologies, and in human nature there will always be meanness – in the same way there’s also always generosity and affection. Which of those emotions becomes manifest depends on institutions.

So those institutions aren’t working very well right now?

Yes, and that’s because of the technology I mentioned before. It allows this franticness, this nastiness to be amplified. New technology allows a meanness which has always been there to be amplified – until controls (or institutions) against it are put in place.

For example, Britain has historically had very good institutions. Churchill didn’t give press conferences from No 10. He would address Parliament, where he could be challenged and criticised by opponents in public, and each side had to listen to the other. Today, there’s the notion Boris Johnson is trying to step over that scrutiny and become more presidential. I’m not saying Boris Johnson is a terrible person – it’s asking too much of any person to not ever be mean or selfish – but if Parliament was working well, he’d be much more moderated and there would be no space for somebody like Dominic Cummings. Churchill had Max Beaverbook on his side, who was a hugely powerful mix of Cummings and Rupert Murdoch, and he would really have done a lot of unpleasant stuff if he had not been blocked by Parliament. At the time, Parliament was very strong: Clement Atlee was in the government and Nye Bevan was in opposition. Bevan was one of the greatest speakers of the 20th century, those speeches were always reported by newspapers, and that system kept the likes of Beaverbrook in check.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

I had a friend once who I wasn't really fair to. It really made me think about how I should try to do better next time, so it was personal experience that triggered me. Once I was triggered, I realised we see this sort of unfairness all the time. As I had kids and they were getting older, I started to think about the sort of lessons we want to tell them. Do we say look kids, it’s a rough world out there and you’ve got to use your sharp elbows? Or is there a way of showing them that yes it’s a rough world, but there’s a way to keep your soul and still advance? That’s what I think the book does: it shows you ten examples of powerful, successful people who didn’t have to use their elbows.

You devote a chapter of your book to the phrase ‘Nice guys finish last’. How accurate is that idea?

I suppose the thesis of the book is that, yes, nice guys will indeed usually finish last, but does that mean you have to be an incredible bully to get ahead? No. There's a position in between. Think of another old phrase, ‘Firm but fair’. Not everybody has to be your best friend, but if they’re fair, you should be happy to trust them and work with them.

Actually, that’s one of the nice things about family life. It’s a rough field out there and nice guys do often finish last, but family is where you can be nice and it’s okay – people won’t take advantage of you. In the real world though, it’s a bit like when you’re in traffic: it’s good to let people in front of you sometimes but, if you always let everybody in front of you, well, you might get by in England or Norway, but in a lot of other countries, you’ve got to push a little bit.

We’ve covered the meanness. What is decency to you?

If I get fired from a job, I'm going to be offended. After a while, if I look at it objectively and can say, you know what, the guy fired me in a fair way – he gave me notice, he gave me a chance to improve and I just wasn't that good at it, or the financial figures were going down and he had to let go of ten people – that guy behaved decently. If, after everything’s calmed down, both sides in a given situation can understand and accept what’s happened, that’s fairness in action.

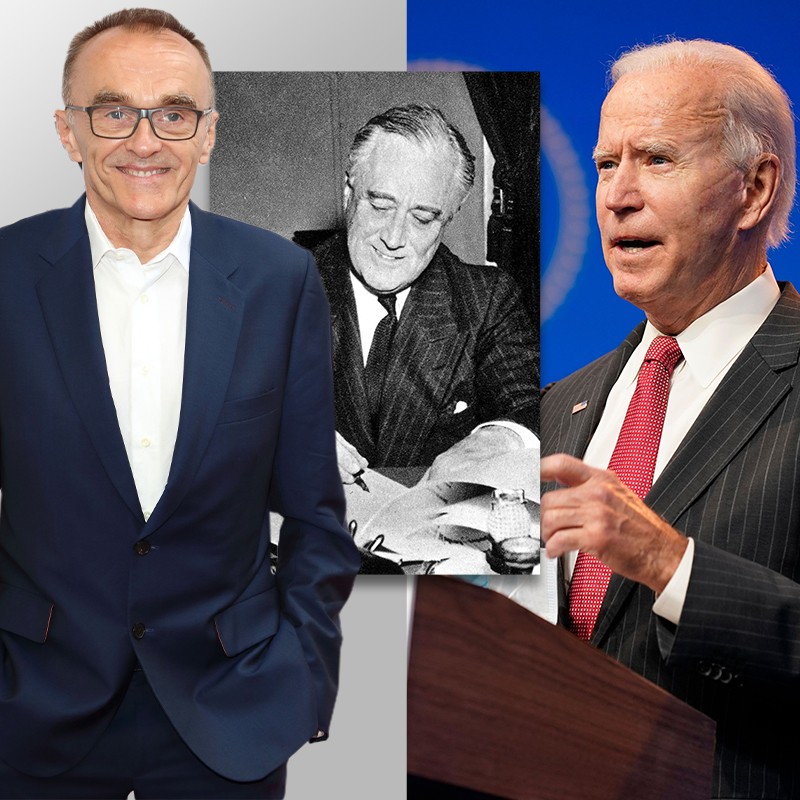

Among the ten heroes of decency you profile in the book, who’s your favourite?

Probably Franklin D Roosevelt. He took a difficult position and just turned it around using these decent tools – without the tools of dictatorship. That’s really very impressive.

Roosevelt is a pretty exceptional person in many ways. Can decency work for anyone?

He was indeed exceptional, but in the book I've tried to cover a range of people from ordinary backgrounds to show this is within our reach. There’s a story involving a pilot from Texas and another one about a construction guy in New York. I’ve also included a quote from the Bible to the effect that the answer isn’t far away; it’s inside all of us. So I do believe decency can work for anyone, but you can’t simply be nice. You have to audit as well as give – to keep an eye on people so they don’t take advantage of you. Decently won success is rare because it’s hard to get that line right.

Is there something beyond just examples from history that convinces you decency can prevail?

Those examples are illustrative and, although success through decency is not super common, there are plenty of other examples. British history is far from perfect, but there are many cases where the British got the line right: they weren’t so soft they were crushed; they weren’t so awful that nobody liked it. Think of the creation of the NHS. Successive governments conceived and continued with the NHS. If they had been totally soft and nice about it, it would never have happened, but it’s also something that could have turned Stalinist and traumatic if they had been bullying about it. They weren’t, it didn’t and now Britain has this incredible medical system in place.

Who is succeeding with decency today?

Joe Biden – possibly. If he doesn’t have a majority in the House of Congress and it ends up blocking him too much, he might not succeed all that much.

How are the rewards of prevailing decently different from the rewards of prevailing in other ways?

If you succeed fairly, you get the reward of gratitude. That gratitude can manifest itself as greater knowledge coming to you. You can also build alliances that will help you in the future.

We’re sold, David. How do we start succeeding fairly?

There are three pillars to succeeding fairly. First, you’ve got to listen. As a leader, put the ego aside and actively welcome information from every source. Second, be prepared to give – because in return you’ll get fuller commitment. Finally, be ready to defend yourself, your team and your project. You will need to be skillful and strategic to see off outside dangers without going too far.

The Art of Fairness by David Bodanis is available to buy here. Find out more about David himself at DavidBodanis.com

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at [email protected].