An Incredible Life Story: Chris Blackwell

I am a member of the Lucky Sperm Club. There’s no two ways about it. I was born into wealth and position, albeit of a particularly mixed sort endemic to Jamaica. I am Jamaican, but I am also English, Irish, Portuguese, Spanish, Jewish, and Catholic. My parents met at a members club in the West End in the 1930s and moved to Jamaica shortly after I was born.

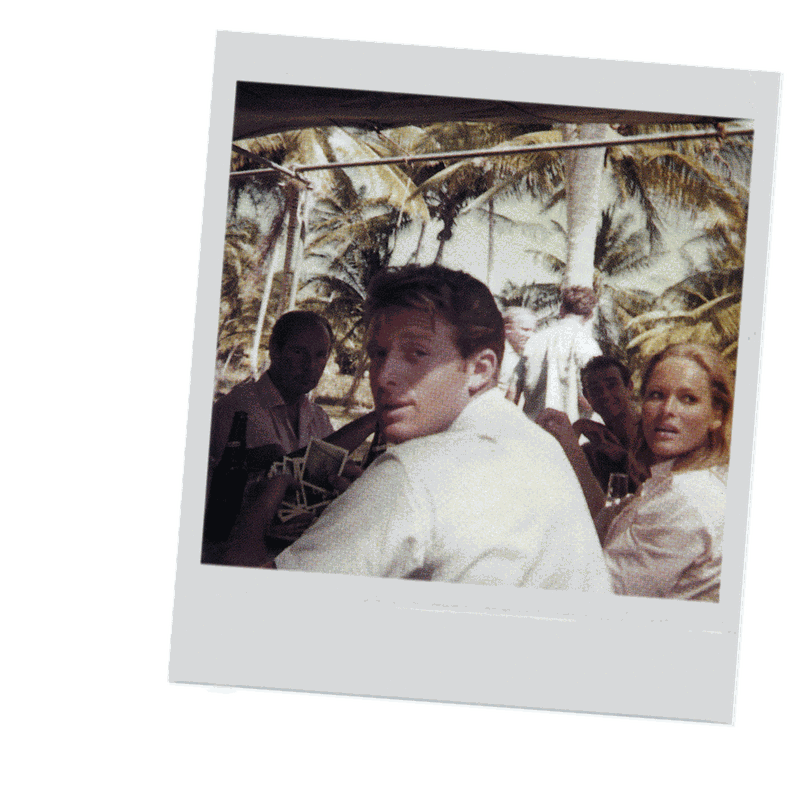

My mum threw glittery parties for the cream of Anglo-Jamaican society. I grew accustomed to mixing among the guests – Ian Fleming, Noel Coward and Errol Flynn became unofficial mentors to me.

My mum was an inspiration for two of Fleming’s most memorable female foils for James Bond: the independent, provocative nature girl Honeychile Ryder, who emerges from the sea in Dr No clad only in a bikini and knife scabbard; and the acrobat-turned-burglar Pussy Galore, who literally took a roll in the hay with Sean Connery in Goldfinger.

Errol Flynn also fancied my mother so he treated me generously. He was cross with me just once, when I was around 18 and tried to steal one of his girlfriends. He was notoriously unfaithful to his own wives, but this didn’t stop him from punching me in the face with all the force of a living legend who had played Robin Hood on the big screen.

I wasn’t a great student. I failed to fit in at Harrow – in one instance, I was caned publicly, in front of the entire student body, which had not happened in 130 years. My offense? Dropping some sweet wrappers on school grounds. In the end, I was not formally expelled. A careful diplomatic solution was reached. ‘Christopher might be happier elsewhere,’ said the headmaster. That was the end of my formal education, at the age of 16. I was sent back to Jamaica, where my adult life awaited me.

I happened upon a freelance job that aligned with my personal interests. One of my friends had the concession in Jamaica for Wurlitzer jukeboxes. I persuaded him to let me lease some of them, which were growing in popularity in the 1950s among Jamaicans who couldn’t afford to keep a radio in their own homes. Before long, I was responsible for 63 of them all over the island. It was one of those jobs for which there were no real qualifications and I was pretty good at it.

Running my jukeboxes was the very best way of discovering on the ground what kind of music people liked. You’d get instant feedback about which new sounds were working and which weren’t. I found myself in crowded tiny rooms where everyone was packed in tight, desperate to hear something new that made their bodies move. If I put on a record they didn’t like, they jeered and I hung my head: the record was a flop. But, if I played something they liked, they were beside themselves, shouting ‘TUNE!’ I loved the real-time market research aspect of it. It was an exhilarating, physical job.

Eventually I felt I had learned enough about records to start making them myself – not only the music, but the actual object. Something entrepreneurial stirred inside me. I felt I was spending too much money buying records for my jukeboxes and it would be worth seeing if I could make my own. The next step was to have my own label.

The very first album I recorded and released on Island Records came out in 1959. I don’t suppose Lance Hayward at the Half Moon Hotel sold as many as 200 albums – and those were mostly in the hotel itself as holiday souvenirs. But working with the band in the recording studio was the moment I decided this was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.

I have sometimes been credited as the man who discovered Bob Marley. But truthfully, no one really discovered Bob Marley. He discovered himself. The atmosphere at the Lyceum in London 1975 was electric, and I saw – and heard – the reaction of the audience to ‘No Woman, No Cry’, and how they started chanting the chorus even before Bob started singing. This was quite a moment – the group hadn’t had a hit yet, but the white post-hippie college crowd was out in force and already knew the Wailers’ songs inside out. At the same time, the venue accommodated a large contingent of blissed-out local black fans, which created a then extremely rare mixed audience. This was a time, remember, when dreadlocks still needed to be described in the mainstream press as ‘waxy plaits’.

As an 18-year-old singer, Bono seemed particularly driven – like he knew what his destiny was and he was charging towards it from a small stage in an unpromising pub in south London. He had some kind of rhythm, even if it was just how he engaged with an imaginary audience. Very early on in these cramped little venues in front of the smallest crowds, he was already clambering over the equipment and up the lighting rig as if he needed to reach out to the back of a vast venue, and even farther.

I saw Bob Marley one last time before he passed, at the clinic in Germany, in a quiet little town near the Austrian border. He had virtually no hair because of the chemotherapy he had reluctantly consented to receive. Only a few straggly bits remained of his mighty dreadlocks. He must have weighed less than a hundred pounds. His life was coming to an end and he knew it. But there was something still there – the something I had noticed when he and the Wailers first walked into my office in 1972. His charisma. His spark. His pride.

/https%3A%2F%2Fslman.com%2Fsites%2Fslman%2Ffiles%2Farticles%2F2022%2F08%2Fslman100822-chris-blackwell-contentmain-2.png?itok=RDB9cUYd)

You can end up being crushed by too big a success. It was while U2 were working on Joshua Tree that I got a dose of reality about why it can be dangerous to have a massive hit group on an independent label. Some investments in film meant that in 1986 I owed U2 many millions of dollars in royalties and Island didn’t have the money to pay them. The label was close to collapse. I had overreached. I was doing too many things at the same time, possibly because, after Bob died, I was always looking for something that could equal what I had with him.

I owned up to U2 about the finances and we managed to figure something out. If they hadn’t trusted me or Island as much as they did, it would have been very messy. Emotionally and financially, though, it was time to sell the label. Once I’d made the decision to let go, I never wavered. In 1989, I sold Island to the Netherlands-based conglomerate Polygram for close to $300m.

As I made money in the music business, I had always invested in property in Jamaica. My mother, Blanche, told me in 1976 that Ian Fleming’s GoldenEye estate was on the market and that I should buy it. For 20 years, it was somewhere private, where I would invite friends and family. At the back of my mind, I thought of it as becoming a hotel and we opened a restaurant there in the mid-80s.

I had always loved hotels. At the end of the 80s, with Island now with Polygram, the hotels became as interesting to me as the music, the idea of making something happen, of finding new ways to meet people and put people together. I’d slowly added cottages to GoldenEye; it wasn’t officially a resort, but it was a place where friends and colleagues could come and visit. Sting wrote ‘Every Breath You Take’ while he was visiting. Steve Jobs celebrated his 29th birthday at GoldenEye.

I got distracted by Miami. I stumbled on a tempting investment project: I was walking along South Beach at the end of the 80s and it seemed most of the buildings were for sale. Filled with retirement homes, flophouses, crack dens, it had a bad reputation. With its dramatic art deco buildings and beautiful architecture, the pastel colours and geometric shapes set against the sun and sea, this was a shame. I started to buy up some of the decrepit deco buildings, including the old Marlin Hotel. We put in a recording studio steps from the ocean and a potent mix of models and musicians crossed paths: U2, Madonna, Beyoncé, Mick Jagger, Aerosmith and Prince all recorded there and celebrities started to turn to up to see what was going on. It became the centre of the transformation.

Around 2003, my film business was in trouble. I was having to sell Miami real estate to make sure I could still protect properties in Jamaica. It was a loss, some of it very emotional, but it ended up being a choice between Miami and Jamaica and there could be only one winner. I wanted to make a difference in Jamaica the way I had along South Beach.

To this day I wake up every morning looking forward to seeing where current projects are – and what new ideas I will think of, sending ripples into the future in a way you can never imagine. I always want to recreate that moment when Bob Marley walked into my office. I don’t want to repeat myself, to be a prisoner of my past. Yesterday’s gone, but I want to come across more moments that lead to change. Because I am useless at doing nothing.

Find Chris’s full story – featuring eye-opening encounters with everyone from Miles Davis to Grace Jones – in The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond by Chris Blackwell. Buy it here.

All products on this page have been selected by our editorial team, however we may make commission on some products.

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at [email protected].