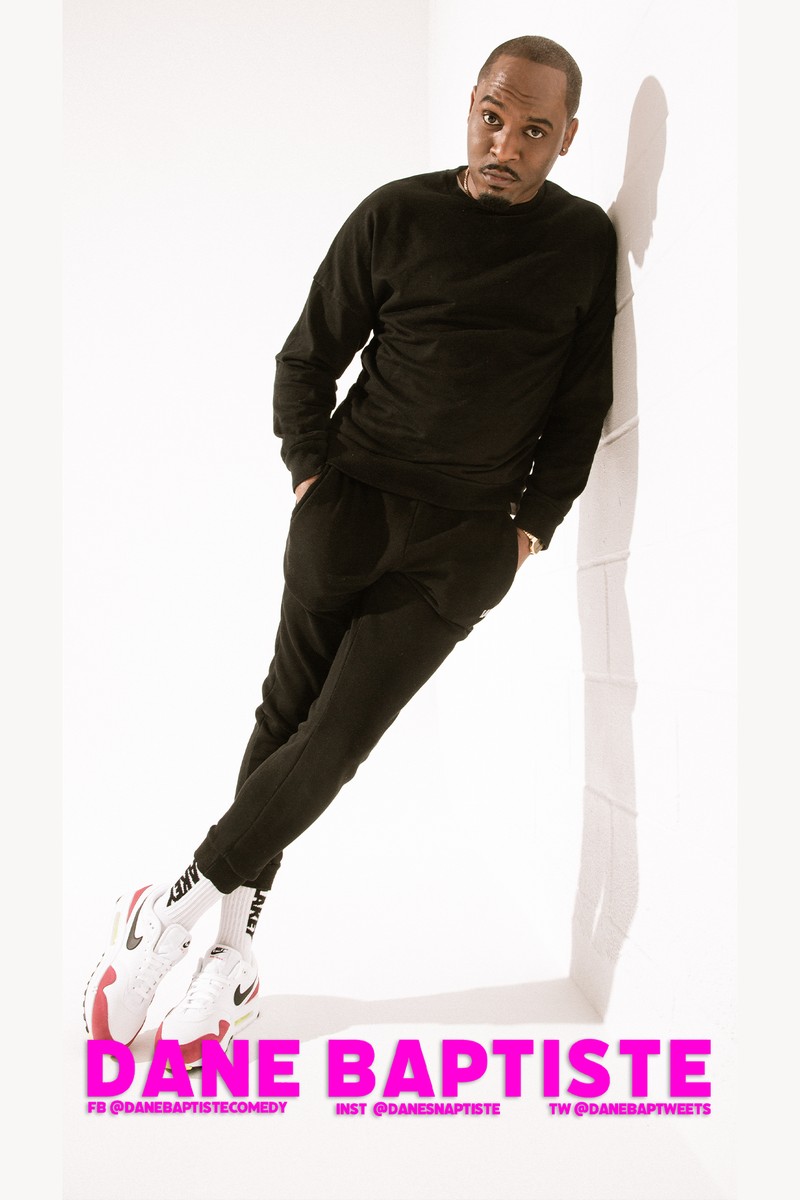

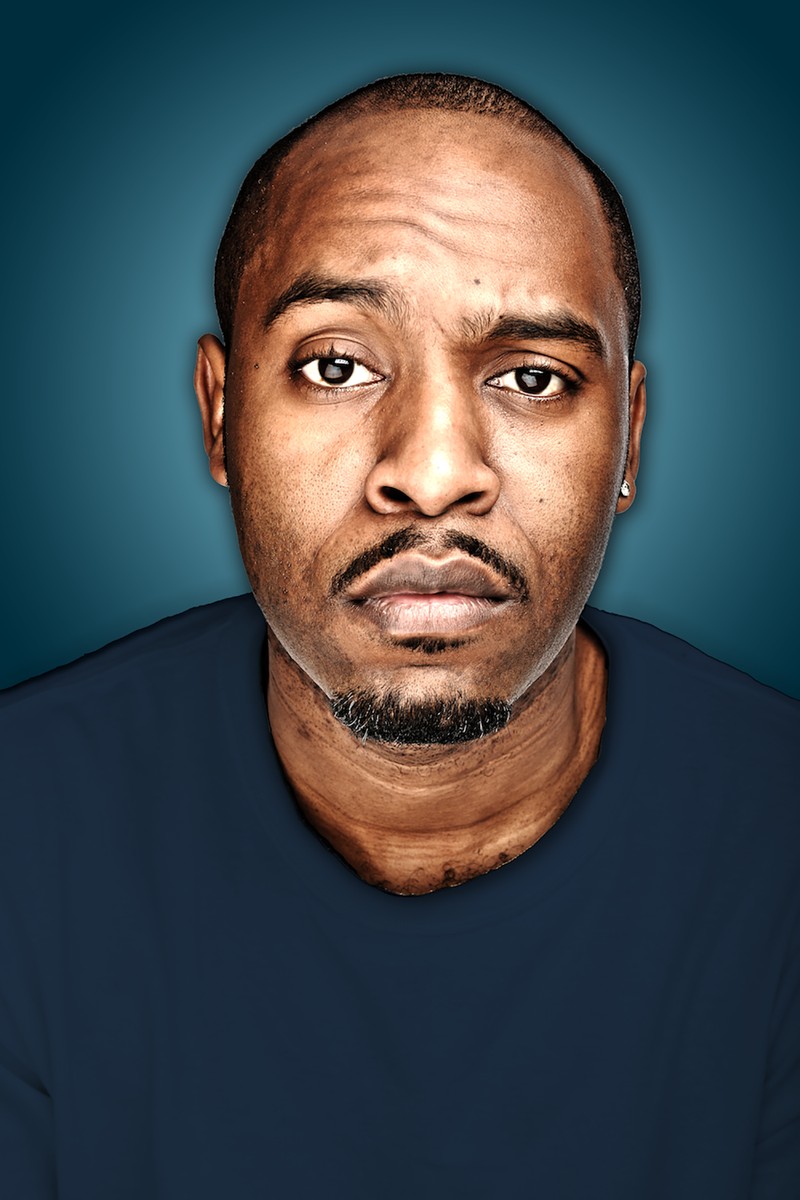

My Life In Comedy: Dane Baptiste

Being funny was a go-to for me when I was younger. I found it helped me in a lot of social situations, especially when I didn’t know many people, or I felt really insecure. It was a quick way of showing people how I felt. Then, on the last day of primary school when I was 11, I remember being told by my sister’s primary school teacher that she didn’t like me and didn’t think I’d go anywhere in life. She told me people were laughing at me, not with me – but I knew she wouldn’t have said it if my jokes hadn’t got to her in some way. That was when it dawned on me that I might have a gift.

Comedy also gave me the chance to act out a bit. At home, I never acted out or played up to my parents. They came from a very traditional Caribbean culture which said children were to be seen and not heard. But, actually, not being allowed to talk very much in the presence of adults taught me to be very observational – which is how I honed my comedic skills. It meant I approached everyday happenings with a bit more critical thought. Observational comedy is an entire genre for a reason – it's about being able to see things other people don’t.

Around about 15, I started thinking about comedy as a career. I’d seen Dave Chapelle and then Chris Rock’s Bigger & Blacker and up until that point, I’d thought comedy was a cliquey club I wasn’t going to be invited into. I hadn’t gone to Rada or Italia Conti, so the performing world felt quite closed off. Then, around 2008, the credit crisis happened, and I realised everything I’d been told about getting a solid and secure job was total rubbish. I remember watching people working honest 9-5s losing everything they’d worked for and thinking, what’s the point when it’s all a f*cking joke?

I’d done a one-off comedy gig a couple of years before which went pretty well. But I still felt pressure to get a ‘real’ job. Then my dad, who had worked on the assembly plant at Dagenham and never missed a day of work, retired after 30 years. They gave him a clock. I’ll say that again – they gave him a clock. I realised there was little point in pursuing a job like that if that’s how you were rewarded. It also dawned on me that the paradigms don’t change between school and the world of work: there are always teachers’ pets, class clowns, people benefiting from nepotism… It was all a complete joke.

I started off on what they call the ‘black circuit’. The gigs I played and audiences that came along meant the material I began with was probably more relevant to the diaspora. It was more nuanced, which was okay, but eventually I found it a bit limiting in terms of the scope. My own taste in comedy was quite eclectic by this point and I was ready to play bigger rooms. I find playing to 3,000 much easier than 300. If fewer people laugh at a joke, you’re less likely to notice in a room of 3,000.

The first big turning point was going to Edinburgh for the first time in 2014. That show ended up earning me a nomination for Best Newcomer – I was the first British black person to be nominated for that award, and it made people notice me. It led to a sitcom I’d written being commissioned by the BBC. That then propelled me into things like Live At The Apollo, which gave me a certain level of credibility in the mainstream, and latterly to the podcast and shows like Bamous.

Another big turning point was the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. It was a weird time – the pandemic was only a few months in – but it gave people time and space to really hear a lot of things that had previously gone ignored. That included all the things I’d been saying in my comedy show. Around this time, I met Howard Cohen – a producer – and we discussed ideas for a new podcast.

People say they find my style of comedy cathartic. Ultimately, comedy is cathartic – both for the comedian and the audience. I usually end up talking about things that piss me off and people, audiences, listeners… They relate to that. They feel like they can let their guard down, and they laugh. It’s like I’m able to say what everyone’s usually thinking. The subject matter we tackle on the podcast feels like a natural evolution of that, with a bit more inquisitiveness and a thirst for knowledge thrown in. I look at it as adding depth that my comedy shows sometimes gloss over.

People often ask me what it was like entering the podcast space – especially as it can be seen as pretty saturated. But it didn’t faze me. Comedy was pretty saturated when I got into it, and that’s even more so the case now. I always say the comedy industry is full of people looking for validation who can’t afford therapy – so as you can imagine, that encompasses a large demographic. But I was confident in my style then, and I’m confident about it now. That’s the difference: you have to believe that what you have to offer is unique enough to stand out. If you believe no one sounds like you, that’s a start. Build it well enough and people will come.

I think the secret to my success is being able to tap into the collective consciousness. If there’s one thing we all do at some point each day – no matter our status or standing – it’s question ourselves, our existence, the meaning of this life, the future of the world. Prepping for a podcast episode for me really isn’t that different to a comedy set. I’m loquacious and good at exchanging anecdotes – so that stands me in good stead. Keeping it fresh is the challenge. But if you can do that, you achieve longevity.

Another key is being able to read the room. What’s the audience like demographically? What’s the pulse? What’s the energy like that night? How are the other comedians before you in the lineup doing and how are they playing it? These are all questions you need to ask yourself if you’re trying to break into stand up. It’s the same with podcasting – the only difference is you’re doing it on a much more intimate level so you can tailor the discussion, so it moves forward in a constructive way.

Podcasts actually play a vital role in our society. That might sound like an extreme thing to say, but I firmly believe it’s a lack of discussion and general conversation which leads to the level of psychiatric help needed in our communities. Not everyone has the money for professional help, and podcasts give people a space to discuss things that worry them or they’re curious about. A lot of conditions people end up being medicated for – anxiety, neuroses – are natural parts of the human experience and podcasts are where people can take advantage of a collective, natural form of therapy.

For anyone looking to break into the industry now, you have to understand that the goalposts have changed. There’s a real intersectionality now between comedy ‘influencers’ and online sketch artists, while established actors can also come across as comedians by having material written for them. I’ve written for Idris Elba, for example. Building a profile is challenging – so don’t do it if you don’t love it. It also doesn’t pay well, and anything you do for long enough gets boring if you’re not passionate about it. Be open, broaden your creative matrix and follow the opportunities.

The London Podcast Festival runs until 19th September. Tickets are available at KingsPlace.co.uk

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at [email protected].